visionOS 26: How Apple Rewrote the Rules of Spatial Computing

The Apple Vision Pro launched in early 2024 to mixed reviews. It was undeniably impressive technology—a feat of engineering that packed remarkable capability into a relatively wearable form factor. But the initial software felt like hardware looking for a purpose. Impressive demos, but everyday use cases remained unclear.

visionOS 26 changes the equation.

Apple’s latest update, previewed at WWDC 2025 and released in late 2025, transforms Vision Pro from an impressive proof of concept into something approaching essential. The focus shifted from “look what this can do” to “here’s how this improves how you work and connect.”

The Shared Experience Breakthrough

The biggest leap in visionOS 26 isn’t about individual use. It’s about shared space.

Previous versions of visionOS let you bring others into your virtual environment through FaceTime, but the experience felt artificial—avatars that tracked your movements but couldn’t really interact with shared digital objects in meaningful ways.

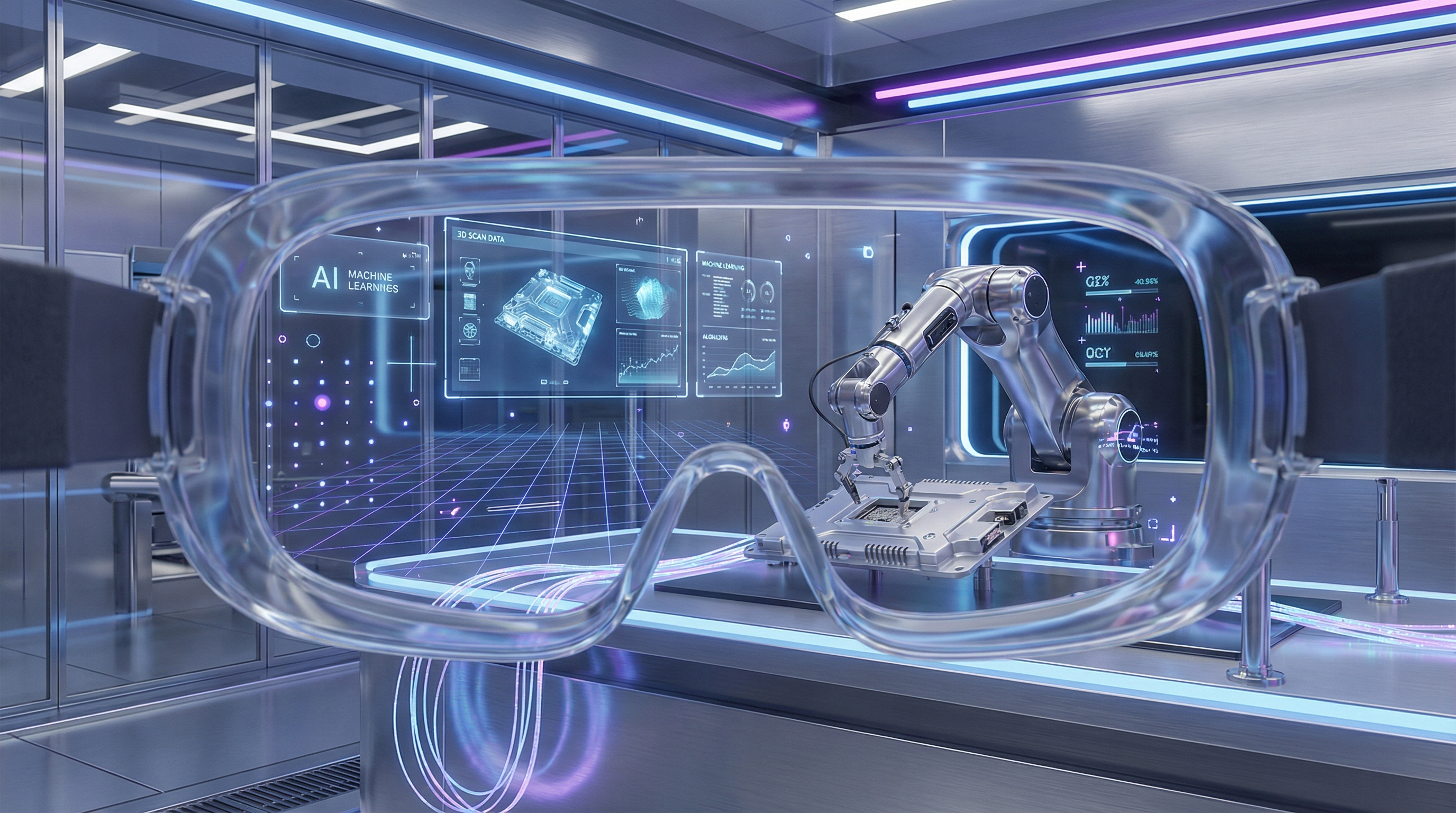

visionOS 26 introduces true shared spatial experiences. Multiple Vision Pro users in the same room can see the same digital objects anchored to real-world locations. Pass a virtual model to a colleague across the desk. Point at a diagram floating in front of you and have it update for everyone present. Build something together in 3D space.

This sounds like a small upgrade. It’s not. Shared spatial experiences fundamentally change what’s possible. Teams that couldn’t collaborate across distances can now work together in ways that feel present rather than mediated. Architects in different cities can walk through a building design together. Medical teams can examine a 3D scan in real-time.

The technical achievement deserves recognition. Apple had to solve problems in hand tracking, spatial anchoring, and low-latency synchronization. Getting multiple headsets to agree on where objects exist in physical space—and keep them stable as users move—is genuinely hard. The fact that it works smoothly in visionOS 26 represents years of behind-the-scenes work.

Volumetric APIs: Apps Get Real

visionOS 26 also delivers on the volumetric promise that spatial computing always hinted at but rarely delivered.

Volumetric apps occupy space around you rather than floating on a virtual screen. Think of it as having floating windows that have actual depth—you can walk around them, view them from angles, and interact with content that exists in three dimensions rather than appearing flat regardless of viewpoint.

The new APIs make building volumetric experiences substantially easier for developers. SwiftUI enhancements include depth alignments for 3D layouts, rotation tools that respond naturally to hand movements, and expanded RealityKit support. What previously required specialized 3D graphics expertise now fits within familiar iOS development patterns.

The practical implications matter more than the technical ones. We’re already seeing volumetric apps that would have seemed impossible two years ago: medical imaging tools that let doctors examine CT scans as manipulable 3D objects, architectural visualization that lets clients walk through unbuilt spaces, educational experiences where students manipulate molecules or explore historical artifacts.

Personas Evolve

The controversial “Persona”—Apple’s attempt to represent you in virtual space—has improved substantially.

Early versions drew significant criticism. They looked uncanny, moving in ways that didn’t quite match real human behavior. Critics called them creepy. Some analysts suggested Apple should abandon the concept entirely.

visionOS 26 takes a different approach: make Personas more expressive and realistic while giving users explicit control over how they’re represented. The improvements in eye contact approximation, hand gesture fidelity, and facial expression tracking are noticeable. But equally important, Apple added controls that let users choose between photorealistic representation, stylized avatars, or traditional video feeds.

The lesson here is instructive: when users reject something, sometimes the answer isn’t abandonment but giving them more control. Not everyone wants to be represented as a digital avatar. Some prefer their actual face. Some prefer something playful. Some prefer to stay on traditional video.visionOS 26 supports all of these, and the result feels less forced.

Enterprise Momentum Builds

The enterprise angle deserves attention because it’s where Vision Pro’s trajectory becomes most interesting.

Initial enterprise adoption focused on training and simulation. Companies used Vision Pro to create immersive experiences for onboarding, safety training, and skill development. These use cases made sense: the immersive quality was compelling, and the cost was justifiable for training that would otherwise require physical equipment or travel.

visionOS 26 expands the addressable enterprise market substantially. The combination of shared experiences and volumetric apps opens productivity use cases that weren’t previously viable. A distributed team can now have meetings that feel more present than video calls without requiring anyone to travel. Designers can collaborate on 3D objects in ways that photos or videos can’t capture.

Major enterprises have noticed. Walmart has expanded its Vision Pro deployment for inventory management and training. Several major airlines use it for maintenance procedures. Healthcare systems are piloting it for surgical planning and medical education. These aren’t large-scale deployments yet, but the trajectory is clear.

The Hardware Gets Better Too

Software improvements would matter less if the hardware hadn’t evolved. The 2025 refresh of Vision Pro—informally called “Vision Pro 2” even though Apple doesn’t use that nomenclature—addressed meaningful hardware limitations.

The new Dual Knit Band, which replaced the original single-band design, substantially improves comfort for extended wear. Early Vision Pro reviews universally complained about the weight distribution; the new design addresses this directly. Battery life also improved, though it remains the primary limitation for all-day use.

The M5 chip, a generational leap from the M2 in the original Vision Pro, enables computational capabilities that weren’t possible before. Machine learning tasks that required cloud processing can now happen on-device, reducing latency and improving privacy. The neural engine specifically optimized for spatial computing tasks makes hand tracking, scene understanding, and persona rendering noticeably smoother.

The Android Question

An important piece of context: Vision Pro remains Apple-only for now, and that limits its addressable market.

Android XR, Google’s effort to create a standard platform for extended reality devices, has made progress but remains fragmented. Multiple Android headset manufacturers have announced or released devices, but none have achieved the ecosystem lock-in that Apple enjoys. The app experience on Android XR varies dramatically by device.

This creates an awkward dynamic for enterprise buyers. Apple offers a consistent platform with high-quality hardware and robust developer support. But it costs significantly more than Android alternatives, and cross-platform development remains challenging. Organizations with mixed device environments struggle to justify Vision Pro investments when their Android headsets can run similar apps.

The resolution of this tension will shape the broader extended reality market. If Apple maintains its quality lead while competitors catch up on developer experience, Vision Pro could become the “iPhone” of spatial computing—premium positioning with ecosystem lock-in. If Android XR delivers compelling experiences at lower price points, the market could fragment in ways that hurt everyone.

Limitations Worth Knowing

Balance the honest assessment with honest limitations.

All-day comfort remains challenging. The best you can reasonably expect is 2-3 hours of heavy use before the headset becomes fatiguing. This limits use cases that would benefit from longer sessions.

The external display—Apple’s attempt to let others see your eyes through the headset—remains a compromise. It works imperfectly, creating interactions that feel slightly off compared to unencumbered face-to-face communication.

Field of view, while improved, still creates a noticeable “looking through windows” effect compared to natural vision. This is a fundamental physics problem that no current headset fully solves.

Battery form factor remains clunky. The external battery pack necessary for current runtimes creates a dangling weight that affects balance. Integrated batteries would improve ergonomics but add weight to the headset itself.

These aren’t failures—they’re the current boundaries of what’s physically possible. But they’re also reminders that spatial computing remains an emerging technology, not a mature one.

Looking ahead

What visionOS 26 represents is less about any single feature and more about the maturation of spatial computing as a platform.

We’ve seen this pattern before. The iPhone launched with impressive but limited capabilities. Each subsequent iOS update expanded what was possible until, years later, the smartphone became indispensable. The same trajectory appears to be unfolding with spatial computing.

Vision Pro in 2026 isn’t the device that will make spatial computing mainstream. That device probably doesn’t exist yet, and it will almost certainly be cheaper and more comfortable than current hardware. But Vision Pro in 2026 is the device that proves spatial computing can be useful today—for specific use cases, for specific users, in specific contexts.

The question for potential adopters isn’t “is this the future?” The question is whether their specific use case has crossed the threshold from interesting demo to practical tool. For many, it has. For many more, it’s getting close.

Apple’s vision for spatial computing is becoming clearer with each update. It’s not about replacing your laptop or phone. It’s about adding a capability that those devices fundamentally lack: the ability to work with digital content that exists in space rather than on screens. That’s a genuine addition to what’s possible. It’s just not for everyone, yet.